Prologue [The Dancing House, Prague]

On 21 June 2018, after returning from my first ever visit to Prague where I went to attend a conference, Africa, local cosmopolitanisms and the world, I tweeted two pictures I’d taken in that city, with the caption ‘#Prague is for dancers’ and a heart-eyed emoticon. The tweet was inspired by the Dancing House – an iconic building on the Vltava waterfront dreamed up by the Croatian-Czech Architect Vlado Milunić – but I’d had plenty of other reasons to think about space, time and movement during my visit. My life revolves around urban movement in and around cities on two continents; in my Twitter by-line, I describe myself as ‘city woman: Africa, Balkans, UK’.

As I walked the streets of the Czech capital, I thought about work, the teaching semester that has just finished, and my own research into Southern African writing, the world, and liquid (though not always dancing) modernities. I encountered images in Prague that stayed with me, that I tweeted. Online colleagues (encountered in person at Ake Festival in Abeokuta, Nigeria in 2016) took note of my tweet and asked for more images and words. Here they are, layered with the words of others.

Prague is for dancers [Liquid Kafka and knitted Marilyn]

Prague is for dancers; it is for those who are beside themselves. In a recent short book on feelings I’ve recently taught to freshers, Stephen Frosh writes about feeling ‘funny-peculiar’ – being troubled by the suspicion that our everyday selves are not as solid and immutable as we think. ‘Quite often’, he writes, ‘we might be talking about a concrete, physical sensation: the body is not working as it should, though it is hard to pin down exactly what is wrong; one is unsettled, awkward, a bit ill, swollen perhaps or off one’s food; just not right.’ [i] Such feelings (of being haunted, as if by an invisible travelling or dancing partner) are best faced in Prague, whose architecture and public art knows how to incorporate the awkward, the swollen and the unexpected. Vlado Milunić’s Dancing House still offends many locals, who prefer the art-nouveau architecture the city is famous for: yet they shrug and say they have learned to live with it. In a central but secluded public courtyard, the gigantic features of Franz Kafka compose and re-compose themselves in a series of random rotations, their metal gleam echoed by the nearby public toilets. Elsewhere, an oversize, knitted Marilyn-shaped sock is pulled over a permanent sculpture by the local artist Josef Malejovskỳ. In this city, a walker is invited to feel at home by feeling out-of-joint.

- 17/11/1989 Plaque

Prague is for small things [Orange sticker, love locks, 17/ 11/89 plaque]

In Arundhati Roy’s God of Small Things, a hired labourer teaches a child the meaning of social hierarchies by re-telling the story of ‘Big Main the Laltain sahib, small man the Mombatti’: big man the Lantern, Small Man the Tallow-stick.[ii] We no longer teach Roy’s first novel to our undergraduates. Two decades on, the high 1990s moment of UK academic Postcolonial literary studies (with which I associate the use of The God of Small Things as a teaching text) is slowly but surely being eclipsed by debates around decolonising World Literature. But I’d teach Roy again at the drop of a hat – not least because I disagree with the early ‘poco’ critics’ griping about the quality of her work. Walking in Prague after the end of the UK teaching season can be a lesson in how easily the difference between big and small things can dissolve. Blink, and you’ll miss: vibrant sticker art, symmetrically placed love locks on a bridge, or a plaque dedicated to the beginning of Czechoslovakia’s anti-communist Velvet Revolution on 17 November 1989 – a clutch of metal hands breaking through a wall, still made to hold (day in, day out): flowers, ribbons, trash, a random umbrella.

Prague is for Afropolitans [Ela]

At the very end of the Asioxe 2018 conference, one of its organisers, Alena Rettova, turned to her co-organiser and life partner, Albert Kasanda, and asked: ‘Are you yourself cosmopolitan or Afropolitan?’ Albert had just given a paper titled ‘Being Africans in the World’, and Alena was asking him to comment on its sub-title (Is Afropolitanism a cosmopolitanism?) from personal experience. Famously deployed by Taiye Selasi in 2005 The Lip, this term (often set alongside Selasi’s subsequent novel Ghana Must Go[iii]) now attracts at least as much debate in transnational literary circles as The God of Small Things once did. Scholars have recognised its limitations, as well as the silencing and omissions it facilitates. Grace Musila, for example, locates her unease with the term ‘in its easy comfort and uncritical embrace of consumer cultures and an equally uncritical embrace of selective, successful global mobility and cultural literacy in the global North.’[iv] And yet, in the home he shares with Alena and their children on the outskirts of Prague, Albert readily enlarged on why his answer to Alena’s earlier question was an unequivocal ‘both’.[v] In the heart of the non-Anglophone ‘new Europe’ (pace the homogenising denominator ‘the global North’), the compound signifier ‘Afropolitan’ enables Albert to claim a complex kind of belonging: both to the unevenly affluent, semi-peripheral heart of post-communist central Europe, and to the Congolese home he has left behind, which is still home to his parents. When I asked what he would lose if he described himself as simply cosmopolitan, Albert simply said: ‘my roots’. For all of its pre-loaded inflections of usage, the term ‘Afropolitanism’ is still open to appropriation. Among other things, it might help seven-year-old Ela Kasandova to situate her Congolese grandmother’s village firmly within Prague’s big and small, graceful and lop-sided, funny-peculiar dance.

________________

- [i] Stephen Frosh, Feelings (Routledge, 2011), p. 28.

- [ii] Arundhati Roy, The God of Small Things (HarperCollins, 1997) p. 89.

- [iii] Taiye Selasi, Ghana Must Go (Penguin, 2013).

- [iv] Grace A. Musila, ‘’Part-Time Africans, Europolitans and ‘Africa Lite’”, Journal of African Cultural Studies 28 (1), p. 4.

- [v] Thanks to Albert Kasanda and Alena Rettova for warm hospitality in Prague and for permission to publish this piece, including a picture of their daughter Ela.

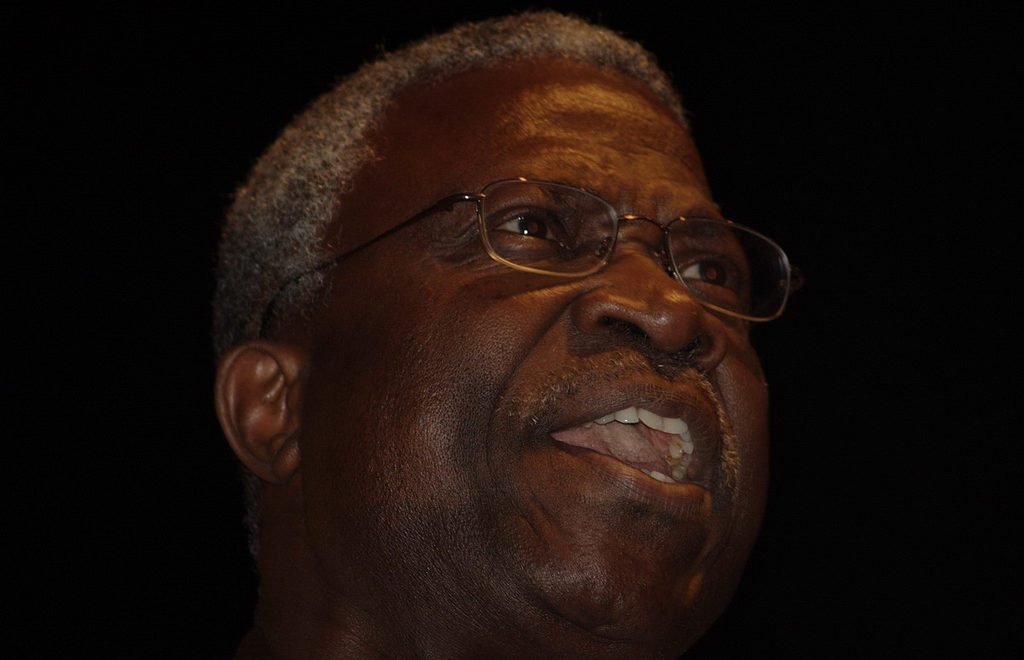

Ranka Primorac is a lecturer at the Department of English, University of Southampton. She teaches and writes about African literatures in English. Together with Steph Newell, she edits the Boydell & Brewer monograph series African Articulations. She is a fortunate tweeter and traveller, and once organised a conference on local cosmopolitanisms at her home institution. She posts pictures of small things on Instagram as @wot_means_switch.

Ranka Primorac is a lecturer at the Department of English, University of Southampton. She teaches and writes about African literatures in English. Together with Steph Newell, she edits the Boydell & Brewer monograph series African Articulations. She is a fortunate tweeter and traveller, and once organised a conference on local cosmopolitanisms at her home institution. She posts pictures of small things on Instagram as @wot_means_switch.